Zero to 400 is a record of my journey from casual observer to (hopefully) confident drone pilot. This isn’t a detailed guide to legislation, and I’m certainly no expert on the ever-changing world of drones. I hope these posts can serve as a guide to the novice pilot and answer the basic questions from anyone interested in drones.

While living in a student house in my early twenties, airborne “toys” were all the rage. A handful of classmates bought cheap quadcopters to spice up days at the park. One of us had the smart idea to buy a tiny RC helicopter, which was mostly used to terrorize the housemate who refused to do any washing up. Working in the aerospace industry, I met colleagues who were into drones, and I was lucky enough to see some of the more expensive models in action for R&D projects.

I don’t remember anyone talking about laws or regulations. But, then again, I don’t remember my mother complaining about nosy neighbours flying over the garden either.

Fast-forward to 2021 and, after a long stint abroad, I’ve just returned to the UK to discover the world of drones has long since moved on. Operator IDs, FRZs, class marks, categories… There’s a lot to learn for the newcomer and a stark contrast to what I’ve seen before.

I’ve decided to document my progress, from complete beginner, to at least somewhat competent in the rules and regulations.

If you’re new to drones, or even visiting the UK with a drone in-tow, I hope this guide proves helpful.

Learning the Drone Code

Before taking any tests or even thinking about buying a drone, I was directed to the Drone Code as a “starting point”. Thanks colleagues for the heads up!

The Drone Code appears to be a summary of all the UK laws and regulations related to drones (and model aircraft). It saves you the hassle of trying to decode all those lengthy legal documents. The Code is published by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and takes the form of a ten-part guide available online.

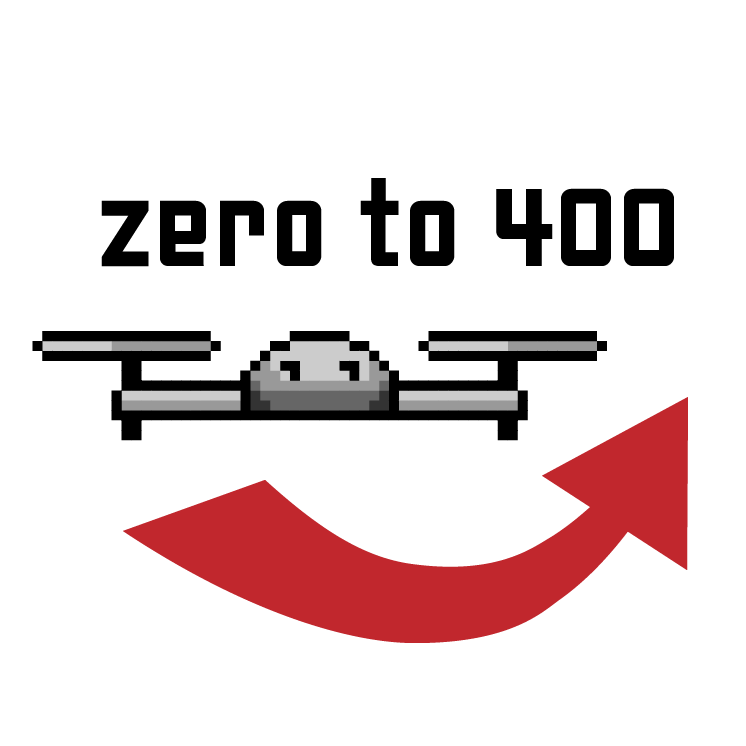

Diving into the first section – Getting what you need to fly legally – and the biggest change since my early drone encounters is the requirement to register your drone. But perhaps the word register is a bit misleading, as what you are actually doing is applying for two different things: an Operator ID and a Flyer ID.

Operator ID

Operator ID

Think of it like a car number plate. Except, you could use the same number on all your cars simultaneously. And it could be either 9 or 17 alphanumeric characters. And it’s registered against your name. And it costs £9 a year. Okay, it’s not quite a number plate, but you get the idea.

Unless the drone is a toy, or it’s really small and doesn’t have a camera, you probably need an Operator ID. Luckily, as mentioned above, you can use the same ID for all your drones. So, the most you are going to pay as the owner of a whole fleet of drones is £9. As an operator, you are responsible for managing and maintaining the drone(s), and you are responsible for making sure anyone you allow to fly them has a Flyer ID (see below). Unfortunately for our younger readers, this is an adults-only registration – so you’ll need to find someone over 18 to register as the operator.

Flyer ID

As well as registering to be the responsible “manager” of the drone, you’re probably going to need a Flyer ID (unless you are only flying very small drones). The Flyer ID is like a driving license, in that it allows you to fly any drones within the classes it covers, not just the ones you own. If you want to fly someone else’s drone, you’ll need a Flyer ID – even if they are the registered operator of that drone. Under 18s can do the Flyer ID too, and there’s actually some great guidance from the CAA aimed at the parents/guardians of drone-flying kids.

The Flyer ID requires passing a short theory test online. Fortunately, it differs from a license in that it’s free, and there’s no practical test involved. Flyer IDs are renewed every 5 years. Let’s assume this is to keep up with any future legislation changes.

Note: You can’t drive a truck on a regular driving license, likewise your Flyer ID alone isn’t going to let you fly really heavy drones. The rules here cover you for most consumer drones like the ones manufactured by DJI – but not all drones. Click here for more info.

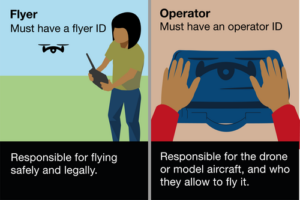

Flying safely and legally

The rest of the Drone Code offers rules and guidelines for safe and responsible flying. Some of the wording is strong and clearly lifted from legislation (you must not fly when under the influence of alcohol, you must not fly over people). Other parts appear to be recommendations, or just things to watch out for (standing out in the sun could affect your ability to concentrate).

Much of the guide feels like common sense, but there are a few rules I wasn’t aware of. For example, you’re given extra leeway on the height limit when flying over a structure, but only if you’ve been asked to carry out some kind of task related to it – like photographing a wind turbine, for example.

Much of the guide feels like common sense, but there are a few rules I wasn’t aware of. For example, you’re given extra leeway on the height limit when flying over a structure, but only if you’ve been asked to carry out some kind of task related to it – like photographing a wind turbine, for example.

The guide has these great little vector illustrations of all the rules, so it’s pretty easy to follow. After about 20 minutes, I feel like I have a basic idea of what can and can’t be done while flying.

I would recommend reading through the Drone Code in its entirety, it doesn’t take too long. The last section of the Code offers links to the full legislation governing drone flight – which includes the EU regulations alongside the CAA’s Air Navigation Order (plus its amendments).

You can find the Drone Code online here: https://register-drones.caa.co.uk/drone-code

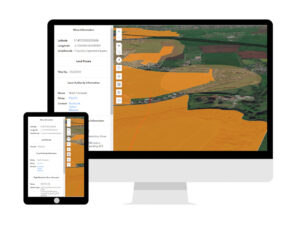

Landowner Permission

Even with a good understanding of the regulations, it’s important to check for bylaws or local restrictions when you fly your drone. Check out The DronePrep Map for everything you need to plan flights safely.

Marketing Manager at DronePrep and recent returnee to the UK after a long stint abroad. Rookie drone pilot, avid writer and lover of all things tech.