Zero to 400, Part 3: Understanding Drone Qualifications

Zero to 400 is a record of my journey from casual observer to (hopefully) confident drone pilot. This isn’t a detailed guide to legislation, and I’m certainly no expert on the ever-changing world of drones. I hope these posts can serve as a guide to the novice pilot and answer the basic questions from anyone interested in drones.

So I’ve read the Drone Code, got my Flyer ID. What’s next?

I would love to dive into a post about getting the hang of controls, or taking great pictures, but before we start that, I’d like to talk about the other qualifications available to both hobbyists and commercial pilots.

Before we look at the certificates themselves, let’s understand why we might need them.

Flight Categories

The CAA (Civil Aviation Authority), who regulate drone use in the UK, have decided to distinguish between different types of drone flight by splitting them into three different categories of flight. These are based on the level of risk in the flight, so they consider factors like proximity to other people, weight of your drone, etc.

These three categories are called Open, Specific and Certified.

The Open Category is for low-risk flights and does not require any special approval from the CAA.

The Specific Category is for higher risk flights and requires operational authorisation from the CAA.

The Certified Category is for even higher risk flights, with larger aircraft and a similar level of regulation and authorisation to manned flights.

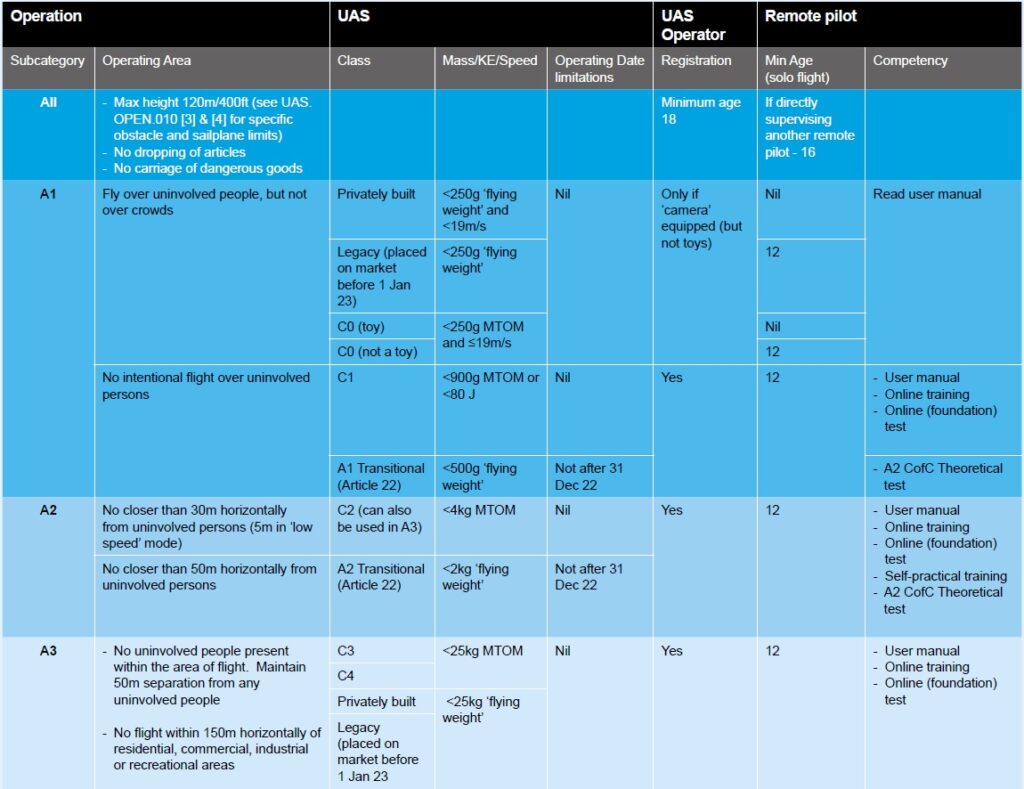

I’m going to wager that the majority of drone flights carried out in the UK fall under the Open Category. The Open Category is divided into three different subcategories – A1, A2 and A3. I’ll try to keep this brief:

A1 – “Fly over people” – very lightweight drones, very low risk.

A2 – “Fly close to people” – lightweight drones, a little more risk.

A3 – “Fly far from people” – heavier drones, but further away.

You can fly most drones in the A1 and A3 categories without the need for extra training – you just need to get your Flyer ID and read your drone’s user manual. The logic here being that A1 is only for very small or toy drones, and A3 is away from the risky spots. There’s a great table here from the CAA that breaks down the different drones and types of flight.

Jump to the last column and you’ll see that for anything in the A2 category, and for one class of drone in the A1 category, you will also need something called an A2 CofC Theoretical Test.

The A2 CofC

The A2 CofC (Certificate of Competency) is a training course and qualification. It consists of four modules and covers the basics of meteorology, the principles of flight and best practice for safety and risk management. Both the course and theory exam can be completed online, with the qualification lasting for 5 years before renewal.

The A2 CofC is popular for pilots who are flying small drones in relatively low-risk areas. It’s quick and cheap to complete – the test takes 75 minutes, costs less than £100 and you can find cheap training courses online. Or you could just self-study and take the exam straight away. Once completed, you are pretty much covered for flying in the Open Category.

If you want to move on to the Specific category, you’re going to need a bit more training.

The GVC

In order to get “operational authorisation” (permission from the CAA) for Specific category flights, you need to have completed another certificate called the GVC.

The GVC (General Visual Line of Site Certificate) is the next level up in drone qualifications. There’s a theory exam and practical test, plus the requirement to create an operations manual and follow the procedures.

The GVC is aimed at commercial pilots flying heavier drones in more high-risk or complex environments. It’s slightly more expensive and time-consuming, but it’s a must-have for pilots looking to fly outside of the limits of the Open category.

Important! This is all really, really new

Something I quickly realised when I started reading about drones is that the UK legislation all changed fairly drastically on 31st December 2020. So from 1st January 2021, there were big changes to the rules and the whole industry is still in a transitional phase as these changes are put into practice. The drone classes (C0, C1, etc.) in the table above aren’t even being used properly yet, as far as I’m aware the manufacturers haven’t yet produced any drones with these marks.

Prior to regulation D-day, something called the PfCO (Permission for Commercial Operation) was the go-to training option for pilots. The CAA used to separate recreational and commercial work in its regulations. Commercial pilots were required to have completed the PfCO in order to fly for work. The CAA no longer distinguishes between recreational and commercial flying when considering pilot training, so in theory you could fly commercially with some drones in the Open Category using just a Flyer ID. One area where there is still a distinction is in insurance – pilots flying commercially must have third party liability insurance for their flights.

If you completed a PfCO before the changes, it will still be valid – so long as you don’t let it lapse. For any new pilots, following the Flyer ID the big options for further training are now the A2 CofC and the GVC.

What else do I need to know?

There’s a lot more to learn about UK drone legislation and how the categories work.

Click here for the CAA’s guide to flying in the Open Category.

Landowner Permission

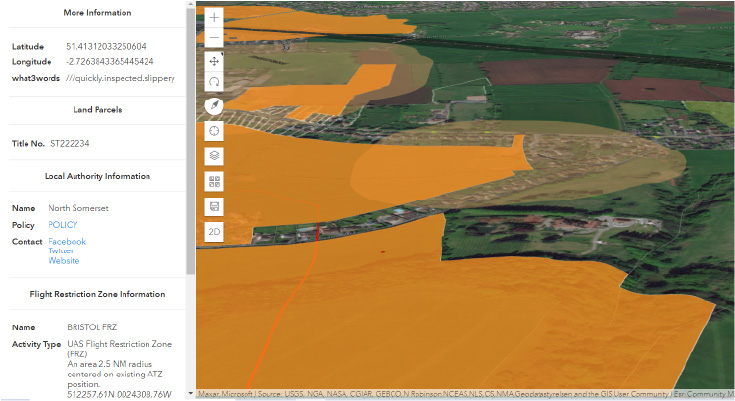

Even with a good understanding of the regulations, it’s important to check for bylaws or local restrictions when you fly your drone. Check out The DronePrep Map for everything you need to plan flights safely.

Marketing Manager at DronePrep and recent returnee to the UK after a long stint abroad. Rookie drone pilot, avid writer and lover of all things tech.

Who builds the software?

Who builds the software? What am I getting with the paid version?

What am I getting with the paid version? I don’t fly every day – should I upgrade to a paid subscription?

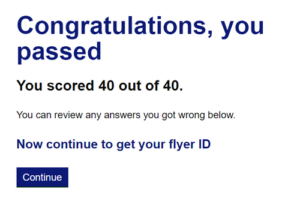

I don’t fly every day – should I upgrade to a paid subscription? Preparing for the Test

Preparing for the Test Some of the questions encourage you to consider the reasons behind an answer (No, because… Yes, because…) and you’ll need to get that part correct too. Imagine I ask you something like: “Should I fly my drone within 20m of a school playground?” and you are offered the answers: “No, because the kids might steal your drone” vs. “No, because flying within 150m of a built-up area is not permitted” – you get the idea.

Some of the questions encourage you to consider the reasons behind an answer (No, because… Yes, because…) and you’ll need to get that part correct too. Imagine I ask you something like: “Should I fly my drone within 20m of a school playground?” and you are offered the answers: “No, because the kids might steal your drone” vs. “No, because flying within 150m of a built-up area is not permitted” – you get the idea. What is Unmanned Air Veterans’ mission?

What is Unmanned Air Veterans’ mission? How does commercial work with drones differ from military operations?

How does commercial work with drones differ from military operations? What are your hopes for the future of the industry?

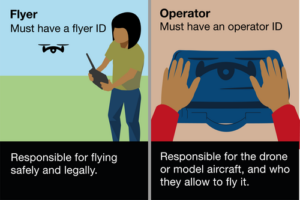

What are your hopes for the future of the industry? Operator ID

Operator ID Much of the guide feels like common sense, but there are a few rules I wasn’t aware of. For example, you’re given extra leeway on the height limit when flying over a structure, but only if you’ve been asked to carry out some kind of task related to it – like photographing a wind turbine, for example.

Much of the guide feels like common sense, but there are a few rules I wasn’t aware of. For example, you’re given extra leeway on the height limit when flying over a structure, but only if you’ve been asked to carry out some kind of task related to it – like photographing a wind turbine, for example.